There was a time when we excelled at dreaming about the future. It was a time when I think we simply needed the future very badly. But there's more to it than that, of course.

During the years of the Great Depression we had lately seen great advances in technologies that affected our everyday lives: the automobile, air travel, and the radio, and then the applications of those basic technologies that had begun to create a world in which less and less of our time had to be spent on the basic labor of keeping our lives going. And it didn't take a futurist to imagine that trend continuing into what seemed like its natural conclusion: a human leisure class - a leisure species! - freed from its daily toil and now able to pursue whatever intellectual or practical pursuits it pleased. We pleased, I mean.

This idea, like everything else, was stood on its head when the Great Depression arrived. But we held onto it - maybe, as I said, because we needed it so much. And what always enchants me about the futurism of those days is its quality of universality. It was seldom about 'what would be better for me'. It was more likely to be about 'what would lead us to a better world'.

Being human, we seldom agreed about what that 'what' was, of course.

Moreover we still believed in the ability of technology to simplify our lives and enrich us. We dreamed up the Greenbelts, which were mixed urban and rural communities - and even built a few! - in the belief that they were the model for a better way to live. We extended electricity to rural areas that still didn't have it. We were paving the way for these futures that were worth believing in.

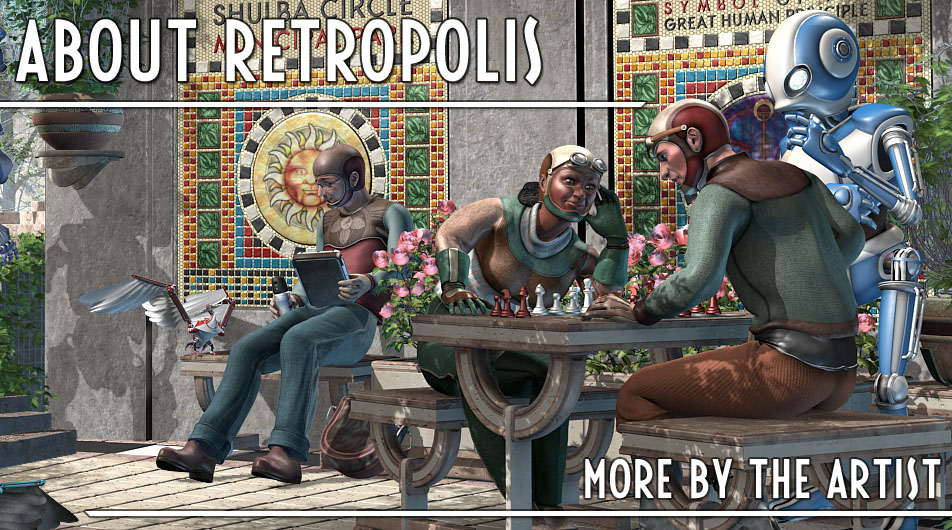

And the picture of that kind of future arrived. It seems to have come from every direction at once. In the 1930s we applied the Streamline Moderne style of Art Deco to anything that would hold still long enough - like appliances - and a lot of things that wouldn't - like trains, cars, and aeroplanes.

The same thing happened to our architecture, and to our entertainments. 1930's Just Imagine, and others that followed, showed us a future where many of these marvels had come to pass.

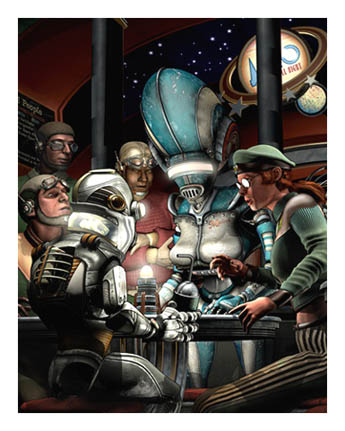

1929 is remembered as the year of the Wall Street crash, but it was also the year when Buck Rogers flew his rocket into our Sunday papers. Flash Gordon was quick to follow, and both of them ended up in the movie serials. Through these hard times the young science fiction magazines thrilled and amazed us with ideas of what the future really might hold.

In looking back on how this vision of the future came together it's clear that all of these very different things fed on each other. They combined to form a futuristic vision that was propelled by need, and heightened by style. It had such a distinct character that it's instantly recognizable, even now - and it was accelerated by a feedback loop in which industrial design, the arts, and the sciences all led us to the image of one amazing World of Tomorrow that seemed so real that it just had to be inevitable.

The Future achieved its shape, finally, at the New York Worlds Fair of 1939. Two of the Fair's most popular attractions were (the original) Futurama and Democracity. Each was a multimedia tour through the Future.

Large parts of this were nothing but corporate propaganda: an effort to teach us to want the new (or newer) cars Detroit offered, and so to want the nationwide system of highways that those cars required. We were fooled into setting aside public transportation, to our great cost. These commercial visions for the Future led not to the universal good, but to what we each might get for ourselves.

In the end we built something sort of like The World of Tomorrow only because its materials and design made it cheap to build. We succeeded in many of the details... but we lost the whole picture. We lost that universal vision for how the world might actually be better, and not just for a few, but for everyone.

And eventually we also lost that hope which had made this most excellent future seem inevitable. We became disappointed with our institutions and with the benefits of technology. At about the time we actually landed on the Moon, we began to think that the future was something to be feared. It's probably no coincidence that in that year of Apollo 11 Buck Rogers parked his comic strip rocket for the last time.

These days our entertainments show us dark, dystopian futures in which the planet's destroyed, or conquered, or just runs out of steam. We don't even always see what caused these apocalypses: what the stories are actually about is the people who live in the wreckage and how that transforms them.

But as we dream these dreams... have a look at the world we're living in. It's nowhere near perfect. But we daily take for granted things that simply didn't exist a few decades ago. And many of those things are good, and have improved our lives. And for the rest....

The best thing about the Future is that we have so much of it. It's always there, just around the corner. It's never too late to try and shape it into something better - not for you and not for me, but for everyone.

If I have an agenda, it's this: I hope that by remembering and enjoying these vintage visions of the Future we'll consider the possibility that our own future might also be full of hope.

Why not? It's up to us. It always is.

Want to send your own site's visitors over here so they can see the retro-futuristic art and merchandise? That's easy. Just visit my banners page for instructions.